Five San men have been arrested by the government of Botswana for hunting in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR). The punitive measure violates their rights as enshrined by Botswana law and a High Court ruling, according to a letter by Stephen Corry, the director of the British NGO Survival International, to the president of Botswana, Mokgweetsi Masisi.

An article on July 12 in a major Botswana newspaper, the Sunday Standard, quoted some of the letter and named four of the five men, all presumably G/wi or G//ana: Tshoganetso Sesana, Monyaku Modumedi, Lefifi Roy, and Tsharae Kelebatseand. Their alleged crime was that they had done some hunting. They were apprehended on May 7, 2020, near New Xade, in the Ghanzi District of Botswana, while they were in possession of some game meat.

Corry’s letter to the president explained that in March this year four men from the small village of Gope, in the southeastern area of the CKGR, had been detained for hunting but were released without being charged. The four named men arrested in May were from Molapo, another traditional village in the reserve. They are due to appear in court in August. Corry’s letter to the president described these acts as disturbing “harassment” of the San people.

Corry said that Survival International hopes the government will uphold the right to hunt by the San people “since their livelihood relies to a large extent on hunting for the pot for their families.” He also mentioned incidents of the government stopping the San from planting melons and other crops in the CKGR. He hoped the government had not devised a policy of preventing gardening by the residents.

The Sunday Standard article went on to review the momentous decision by the Botswana High Court in December 2006 in favor of a suit brought against the national government seeking to reverse a policy that terminated food, water, and health services to San living in the CKGR. As news stories from that period indicated, the suit against the government seeking to guarantee the rights of people living in the reserve was upheld by the court.

The court ruled that the government was no longer allowed to prevent San who had lived and hunted in the CKGR from continuing as they had always done—living and hunting there. It also said that by no longer issuing hunting licenses, and by preventing their supply of food rations, the government was, in effect, condemning the San to starvation, which would violate the national constitution.

The court also decided that the government’s policy of requiring the San to obtain permits in order to enter the CKGR was unconstitutional and unlawful. It stated that since the San had the lawful right to be in the reserve, the government’s attempts to prevent them from entering it was illegal.

It is distressing to learn that the G/wi are still subject to discrimination by government officials in Botswana—that the passage of time has not done much to erase hostile feelings toward the minority people. But the British human rights NGO and the Botswana newspaper deserve credit for pointing out to the power elites in the nation that existing laws and rulings do protect their indigenous minority citizens.

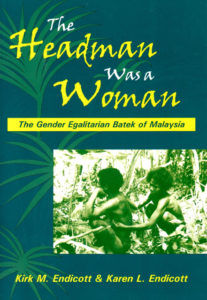

The “headman” of the band was a woman named Tanyogn, a born leader of her community. A middle-aged, energetic individual, at times she had to strenuously advocate for her people by confronting outsiders. For instance, one day outside traders tried to blame the Batek because some cut rattan had floated away on a flood. She shouted at them that they were the fools who had piled the harvest on the bank of the river. The Batek, she said, would have had the common sense to pile products like that safely in the forest.

The “headman” of the band was a woman named Tanyogn, a born leader of her community. A middle-aged, energetic individual, at times she had to strenuously advocate for her people by confronting outsiders. For instance, one day outside traders tried to blame the Batek because some cut rattan had floated away on a flood. She shouted at them that they were the fools who had piled the harvest on the bank of the river. The Batek, she said, would have had the common sense to pile products like that safely in the forest.