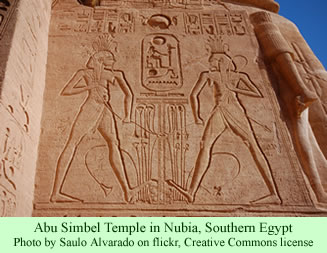

The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting published an interesting report last week by multimedia journalist Lauren E. Bohn on the Nubians of Egypt and their continuing claims to lands along the Nile.

The text of her article offers little that is new: the losses the Nubians suffered since the Aswan High Dam was closed in 1964; the forced relocations of most of the villagers; the lack of adequate compensation to the people; and the language and customs that are dying. She mentions the discrimination that Nubians have faced at the hands of Arabic Egyptians, and the lower status, menial jobs that many take in Cairo and other Egyptian cities.

The text of her article offers little that is new: the losses the Nubians suffered since the Aswan High Dam was closed in 1964; the forced relocations of most of the villagers; the lack of adequate compensation to the people; and the language and customs that are dying. She mentions the discrimination that Nubians have faced at the hands of Arabic Egyptians, and the lower status, menial jobs that many take in Cairo and other Egyptian cities.

The prime interest in her article is the series of 19 photos that accompany the story, especially the ones that portray individual Nubians and the communities where they live. A few should be singled out, so people interested in the peaceful Nubian culture can visit the site, look through the images, and read the captions she provides.

The first, the image that is pictured when the story opens, shows a dun-colored, one story building with an elderly lady sitting on a bench in front. Bohn tells us that she is Umm Ahmed, a lady who clearly remembers when she and the rest of her family were removed from their village in 1964. The journalist goes on to relate, in the caption, that the government now in power, the Muslim Brotherhood, is promising a “strategic vision” for the development of the Aswan Governate, but the Nubians are skeptical.

Photos two and three portray 82-year old farmer Hag Gaffour, who is shown in front of his fields near Abu Simbel and then in front of a masonry wall. He explains that he was lucky that his family was displaced onto viable agricultural land. He tells the journalist that he is not sure it is worthwhile for Nubians to keep on fighting for their rights. Many are becoming tired of it all.

“Yes, we are a minority, but we’re also indigenous people,” he argues. “Nubians have lived on this land for thousands of years.” He goes on to say that they have suffered from a lot of discrimination, but, even worse, they are ignored and neglected—“like we’re not even here,” he complains.

The photos give a good impression of the rural countryside. No. 4 shows a couple men walking away from the camera along a flat, sandy country road. No. 6 shows a family herding a flock of goats across another country road, apparently at the edge of a village in the background.

Images 9 and 13 show lovely scenes in the village of Abu Simbel—carefully tended buildings and roads kept neat and clean to appeal to tourists. It is refreshing to see photos of the homes where contemporary people live, rather than just the stone colossi of a dead pharaoh and his wife that have been photographed by countless tourists over the years.

Perhaps the most appealing images are the portraits, and the accompanying quotes, of the Nubian people themselves. Hagg Essam is quoted (no. 7) complaining that the two million Nubians are not effectively represented in Egyptian politics. All the parties court them in the run-up to each election, but then they leave and don’t come back. “They don’t care,” he says.

Ms. Bohn pictures Ahmed Hussain (image no. 10), the 70-year old owner of a school in Alexandria who frequently visits Nubia, where he hopes to build another school. His attitude is that Nubians have to help themselves, and not rely on assistance from the Egyptian government. “Let’s just work,” he urges.

The next image (no. 11) is of Hussein Kobbara, who is working on a Nubian language dictionary. The following image (no. 12) is of the Mayor of Abu Simbel, Mubarak Ahmed Aly. He advocates the construction of a new highway south from Abu Simbel into Sudan, so that his community can become a crossroads trading center. “We’re more than just temples and tourism,” he argues.

Bohn fills in the details about Abu Simbel: that only government controlled busses are allowed to bring visitors to the tourist center once a day—a scheme by the government to make money, she suggests.

Image no. 16 shows Nasser Basho and his daughter Fatmah, presumably pictured in their home. He is a director of plays and musicals. He explains that, for him, music is his way of life, his way of revolting.

Image no. 19, showing a somewhat trash-strewn urban street, includes a caption about the land question. Bohn indicates that some Nubians, like the writer Kobbara (pictured in image 11), express the importance of remaining hopeful about the issue. “There is so much, so much potential. We can see it, but we cannot reach for it,” Mr. Kobbara says.

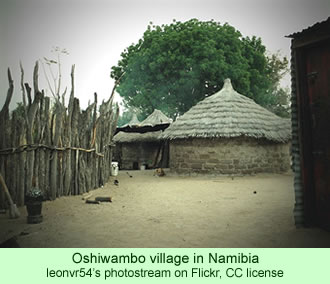

The existing colony, Valley View, was founded in 1971 near the rural hamlet of Torrington, AB, about 55 miles north of Calgary, 33 miles south of Red Deer, 20 miles east of Olds, and 45 miles northwest of Drumheller. It is preparing to split off a daughter facility to be called the May City Colony. The new colony will be about halfway between Olds and Torrington. A few buildings have been erected for the new facility, and a handful of men are already handling some plant operations on the site, which Mr. Stahl shows the reporter.

The existing colony, Valley View, was founded in 1971 near the rural hamlet of Torrington, AB, about 55 miles north of Calgary, 33 miles south of Red Deer, 20 miles east of Olds, and 45 miles northwest of Drumheller. It is preparing to split off a daughter facility to be called the May City Colony. The new colony will be about halfway between Olds and Torrington. A few buildings have been erected for the new facility, and a handful of men are already handling some plant operations on the site, which Mr. Stahl shows the reporter.

A

A