One of the most significant issues confronting students of peace is how, or if, it is possible for a peaceful society to retain its values in the face of violence in the surrounding nation state. That question should be uppermost in the minds of people concerned about the Nubians of southern Egypt, who live in the midst of turmoil after the voting in a second round of elections this past week.

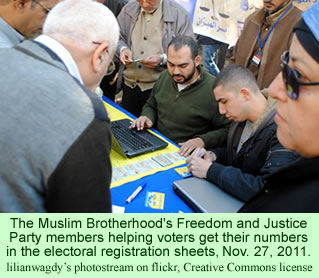

Numerous political parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, the best known, have been competing for support from Egyptians. News reports have indicated that demonstrators have staged massive, violent street protests against the appointment of the new prime Minister, Kamal Ganzouri, by the interim military rulers of the country. Ganzouri criticized the violence of the protesters, and urged them to concentrate instead on rebuilding the economy and the nation. The protesters fought with police and military forces in central Cairo, and many people claim that protesters have been killed by live ammunition, though officials have denied that charge.

Numerous political parties, including the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, the best known, have been competing for support from Egyptians. News reports have indicated that demonstrators have staged massive, violent street protests against the appointment of the new prime Minister, Kamal Ganzouri, by the interim military rulers of the country. Ganzouri criticized the violence of the protesters, and urged them to concentrate instead on rebuilding the economy and the nation. The protesters fought with police and military forces in central Cairo, and many people claim that protesters have been killed by live ammunition, though officials have denied that charge.

The broader, and better, news from Egypt last week has been that the second round of elections were being conducted across the country. The Nubian community has been actively voting for representatives that might support their agendas. One of many parties contending for support, the Revolution Continues Alliance, is headed by Abdallah Abdel Fattah, a Nubian. However, the Nubian people of southern Egypt appear to be voting for another group, the Egyptian Block, according to an activist and observer from their society, Ahmed Ragab.

Mr. Ragab believes that the Freedom and Justice Party is the second choice for Nubian voters. The Salafi Al-Nour party has also gotten some Nubian support. Ragab felt that Nubians were likely to vote for an independent candidate named Adel Abu Bakr, a prominent advocate for their issues.

Nubians had hoped that they might gain some special recognition when the new voting districts were established before the elections. They wanted their own constituency in order to guarantee that they could have at least one Nubian in the new parliament, but that did not happen. The Aswan Governate, in which most Nubians live, was allocated six seats in the new parliament, of which four were to be elected through the party lists system while two others were single winner seats.

Last month, Nubian protesters returned to the streets of Aswan, repeating their oft-made demands, that they be guaranteed the right to return to at least some semblance of their historic communities near the Nile River, which were flooded and destroyed by the Aswan High Dam in the 1960s. Protests about this issue had become violent in early September. A spokesperson for the Nubian Democratic Youth Union, Yahia Zaied, told the press that Nubian protesters were still making their demands.

They were angered when they realized that their hopes for a voting district of their own had been ignored. The ruling military power in Egypt, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, had in fact promised them earlier that they would have their own independent constituency. The Nubians were also angry because the military and security forces had violently broken up the Aswan sit-in, beating the protesters and removing their tents.

Thus, events have revived the question once again. Can a people who cherish the nonviolent resolution of conflicts retain their values when military and police forces beat and intimidate them? Gandhi’s answers would have been clear on the issue, but the Nubian situation is difficult.

Overcoming skepticism and convincing people of the value of studying peaceful and nonkilling societies is one of the central concerns of the members of the Research Committee—prominent anthropologists and scholars who express a firm belief not only that nonkilling societies exist, but that their examples can be useful to peoples worldwide. The basic agenda for the day was to explore ways of further promoting this message. Thomas Fee from the Center for Global Nonkilling (CGNK)moderated the session.

Overcoming skepticism and convincing people of the value of studying peaceful and nonkilling societies is one of the central concerns of the members of the Research Committee—prominent anthropologists and scholars who express a firm belief not only that nonkilling societies exist, but that their examples can be useful to peoples worldwide. The basic agenda for the day was to explore ways of further promoting this message. Thomas Fee from the Center for Global Nonkilling (CGNK)moderated the session. “Challenging the Legacy of Innate Depravity: The New Tidemark of the Nonkilling Paradigm,” the panel organized by Prof. Les Sponsel and the

“Challenging the Legacy of Innate Depravity: The New Tidemark of the Nonkilling Paradigm,” the panel organized by Prof. Les Sponsel and the

The paper by Gomes, who is from La Trobe University in Australia, explored those ideas at the panel session “Challenging the Legacy of Innate Depravity: The New Tidemark of the Nonkilling Paradigm,” which was part of the American Anthropological Association’s annual convention in Montreal last month. The paper session was sponsored by the

The paper by Gomes, who is from La Trobe University in Australia, explored those ideas at the panel session “Challenging the Legacy of Innate Depravity: The New Tidemark of the Nonkilling Paradigm,” which was part of the American Anthropological Association’s annual convention in Montreal last month. The paper session was sponsored by the

Endicott’s paper, “Peaceful Foragers: The Significance of the Batek and Moriori for the Question of Innate Human Violence,” was of particular interest for this website because of its careful review of Batek peacefulness. He opened by giving credit to Douglas Fry, who had gotten him involved in comparing two different hunting and gathering societies and linking those comparisons with the development of human behaviors.

Endicott’s paper, “Peaceful Foragers: The Significance of the Batek and Moriori for the Question of Innate Human Violence,” was of particular interest for this website because of its careful review of Batek peacefulness. He opened by giving credit to Douglas Fry, who had gotten him involved in comparing two different hunting and gathering societies and linking those comparisons with the development of human behaviors. On

On  The best way to begin alerting visitors to this website about the work of the CGNK is through a review of the book

The best way to begin alerting visitors to this website about the work of the CGNK is through a review of the book