The Okapi Conservation Project (OCP) has declared Friday, October 18, as World Okapi Day and has asked fans of the rare mammal to help spread the word. The project is particularly focused on generating enthusiasm for protecting the animals among school children. A side benefit would be to foster awareness of the plight of the Mbuti, who live in the Ituri forest along with the okapis.

The website announcement of the special day for celebrations explains that while the okapi is a cultural symbol of northeastern D.R. Congo, its existence is endangered by poaching, slash-and-burn agriculture, and illegal gold mining in its home range. The okapi is a horse-size mammal related to the giraffe. The only wild population of the animals in existence occurs in the northeastern Congo rainforests.

The fate of the okapi is often linked in press reports to that of the Mbuti—both live in the same forest and both are subject to murderous hostilities from a wide range of outside interests. An article four years ago discussing the violence affecting both people and wildlife said that around 30,000 okapi used to live in the Ituri Forest but by March 2015 that number had dropped in half. Another article published in January this year indicated that the number has further dropped to an estimated 10,000 animals.

The Okapi Wildlife Reserve, a 5,300 square mile UNESCO World Heritage Site in the Ituri Forest dedicated to protecting the okapi and other wildlife, is located just outside Epulu, the community where scholars have focused their research on the Mbuti and the okapi. But studying the rare animals—or the indigenous people, for that matter—is quite hazardous.

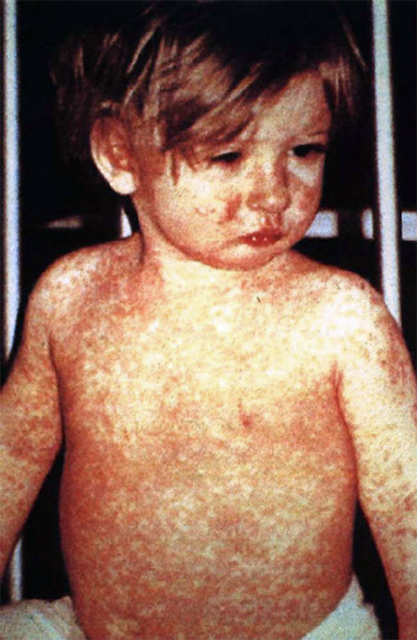

Armed militias murder villagers with impunity, illegal mining operations carry on their brisk trade in minerals that are in high demand on world markets, and poachers take out animals for bush meat and for the ivory trade. Compounding the problems, the communities around the Ituri Forest are suffering from a spreading plague of the Ebola virus. Visitors to the northeastern Congo are either crazy or highly dedicated health workers.

The World Okapi Day website indicates that preserving the culture of the Mbuti is just as important as protecting the okapi. After all, they have lived together in the Ituri Forest for 40,000 years. World Okapi Day provides a good reason for the local Mbuti to perform their dances, thus encouraging them to preserve their traditional culture.

The special focus of the World Okapi Day is on getting children to take an interest in the animals. Organizers will go into villages in the Ituri region and conduct sporting matches, races, and other events with built in messages about protecting the forest and its rare animals. Conservation information will be shared in the schools. Prizes such as school supplies and backpacks will be awarded to the children in hopes that they will take the conservation ideas home to share with their families.

While the website focuses on the okapi and the Mbuti, it also lists numerous organizations and zoos around the world with which the OCP has partnered. The OCP welcomes support from anyone who wants to help preserve a rare animal—and, by extension, an endangered peaceful society.