The lush green and brown farmlands of central Lancaster County and the lives of the Amish and Old Order Mennonite farming families who live there are seriously threatened by a proposed development. Opponents of the development claim that the horse and buggy culture of the Plain People will be disrupted if not destroyed by all the traffic that the project will bring into their rural Manheim Township community.

An article published last Thursday in Philly.com provides details about the controversy. It indicates that the developers want to build 550 homes plus a restaurant, hotel, banquet hall, convenience store and supermarket on a 75-acre tract located on the Oregon Pike, PA route 272, a few miles north of U.S. 30 and the city of Lancaster. Main roads like U.S. 30 are already crowded with traffic but this development will threaten the horses and buggies of the Old Order folks on the narrower, back country roads.

Supporters claim that the development, to be called Oregon Village, will bring fresh commerce, new housing, and much-needed revitalization into the township. An important selling point in their view is that it would bring in $3 million per year in new tax revenues. And, the argument of developers everywhere, it would create jobs.

Mary Haverstick, the co-founder of Respect Farmland, a local citizens’ organization, expressed the opinion that the proposed development would be just like “plopping a small city in the middle of farmland.” The critics argue that the development would completely destroy the lifestyle of the Plain People and would signal the beginning of the end of bucolic country life in the county.

The village of Oregon, located along route 272 in Manheim Township, with about 50 houses at present, would balloon to over 550 dwellings. The resulting surge in the number of vehicles on the roads would threaten and perhaps end the horse and buggy traffic and the culture that goes along with it.

Amish farmer Amos Beiler spoke frankly to the reporter while standing in a field in the township. He said that he couldn’t imagine taking his horse and buggy out onto a six-lane highway. He admitted he was undecided about the proposal: “I just don’t know how it’s going to work,” he said.

Supporters of the project say that traffic can be detoured away from the smaller roads; detractors suggest that it will be a nightmare for the Amish and Mennonites. Pamela Haver, a cousin of Mr. Beiler’s, was blunter than he was: “It’s a disaster waiting to happen,” she said. Both the developer and the opposing groups have hired law firms to represent them in the contest.

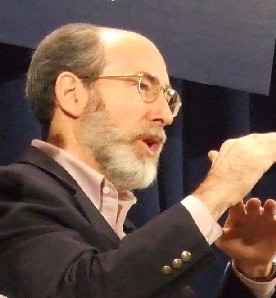

A different article about the same controversy published two weeks ago revealed that some Amish farmers in Manheim Township approached Donald Kraybill, famed authority on the Amish, for his take on the issue. The retired faculty member at Elizabethtown College, who is a senior fellow emeritus at the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies, expressed the thought that the development might provoke concerns for the First Amendment rights of the Amish.

“It could be seen as a detriment to their ability to practice their religious faith because their churches stipulate that they use horse-drawn vehicles,” Kraybill said. He went on to say that, in time, the Amish could leave the area if the project is indeed built. After all, it is proposed for the middle of one of their communities, which justifies their special concern about it.