A tragedy this summer involving a pregnant Fipa woman who was denied permission by a fancy resort in Tanzania from seeking medical help and died as a result, continues to merit news coverage in Africa.

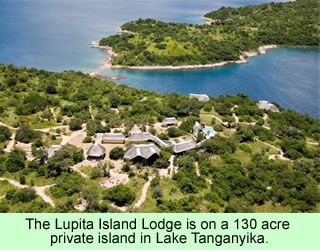

The back story is that the woman was traveling with companions along the shore of Lake Tanganyika heading for a hospital when large waves rose up and they sought safety on shore. They happened to land at the property of the Lupita Island Lodge and pleaded for permission to go on to the nearest hospital by land. The lodge has a rigid policy of chasing away all intruders with fierce dogs, in order to protect their wealthy guests. The tourists pay large amounts of money per night to stay in villas with spectacular views of the lake, unimpeded by any walls. The guards chased the travelers away and the woman died, along with her fetus.

The back story is that the woman was traveling with companions along the shore of Lake Tanganyika heading for a hospital when large waves rose up and they sought safety on shore. They happened to land at the property of the Lupita Island Lodge and pleaded for permission to go on to the nearest hospital by land. The lodge has a rigid policy of chasing away all intruders with fierce dogs, in order to protect their wealthy guests. The tourists pay large amounts of money per night to stay in villas with spectacular views of the lake, unimpeded by any walls. The guards chased the travelers away and the woman died, along with her fetus.

Local people were intensely angered by the arrogance of the lodge owner—it appears as if wealthy foreigners mean more than the lives of local people—so they started to protest. A further story in August revealed that a variety of allegations had been made about criminal behavior by the lodge management, such as gun running and trafficking in live animals. The administrator of the Rukwa Region of Tanzania, Ms. Stella Manyanya, said these charges were being investigated.

A news story published at the beginning of last week indicated that local people continue to agitate about the attitudes of the lodge management, and charges of illegal activities at the lodge are still being raised. The latest is that the owner of the lodge, Mr. Tom Lithgow, a Tanzanian citizen of British origin (earlier reports had indicated he was an American), has allegedly been evading taxes.

The Tanzania Revenue Authority in Arusha is investigating. Mr. Philip Kimune at that agency said that whistle blowers in the Nkasi District of the Rukwa Region have reported the supposed tax evasion to the TRA. Mr. Kimune said that he has instructed local TRA officials to visit the lodge and examine their records, and he has told one Tanzanian news source that he will personally visit the Lupita Island Lodge. He indicated he has been in contact with the lodge owner and has been told that the lodge will cooperate with the investigation.

Peti Siyame, the reporter of this story, wrote that he tried to get some clarification from the lodge about the tax evasion charge, but the lodge management refused to discuss the situation with him.

Last month, the national Minister for Lands, Housing, and Human Settlement Development, Prof. Anna Tibaijuka, announced that she was investigating the legal status of the ownership of the lodge facility. She informed the reporter that her ministry considered Mr. Lithgow’s ownership of the property to be illegal since agency personnel had not found any documents indicating that he did, in fact, own it.

Another national official, Aggrey Mwanri, the Deputy Minister of State in the Prime Minister’s office for Regional Administration and Local Government, directed Ms. Manyanya, the Regional Commissioner, to thoroughly investigate the problems at the lodge. Mr. Mwanri ordered officials in the regional government to investigate the allegations of the sale of arms across the lake to the DR Congo. His comments were prompted by local complaints, aired at a public meeting, that the lodge owner was humiliating them.

Mr. Mwanri also announced, at the public rally, that he had banned the lodge from restricting local residents from fishing in the lake near the lodge, or preventing them from going near the property. Ms. Manyanya apparently said that it was too soon to comment about the arms smuggling allegations, though, she said, “this allegation needs serious investigation.” She had said the same thing, of course, three months earlier.

It is clear that local residents, many of whom are of Fipa origin in that area, are not about to easily give up their vendetta against the rich man who owns the elite lodge. His employees kept out the wrong people and caused a tragedy over three months ago.

The

The