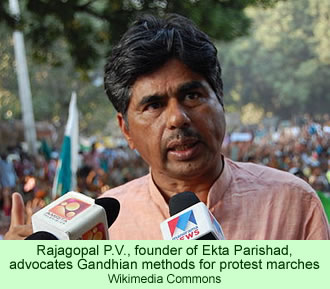

A peaceful protest march by tens of thousands of poor, landless, tribal peoples toward Delhi ended last Thursday in Agra when the government of India agreed to meet the demands of the marchers. The Rural Development Minister, Jairam Ramesh, signed an agreement with the march organizer, the NGO Ekta Parishad, that was quite similar to one he had refused to sign earlier, as reported in the news the previous week.

As the marchers slowly made their way toward the capital last week, the government began to cave in to most of their demands. They had left Gwalior on Wednesday, October 3, planning to arrive in Delhi on October 29. On Wednesday, the 10th, the news broke that Mr. Ramesh was going to meet the march in Agra the next day, a little less than halfway to the capital, with new proposals—and apparently a renewed willingness to negotiate.

As the marchers slowly made their way toward the capital last week, the government began to cave in to most of their demands. They had left Gwalior on Wednesday, October 3, planning to arrive in Delhi on October 29. On Wednesday, the 10th, the news broke that Mr. Ramesh was going to meet the march in Agra the next day, a little less than halfway to the capital, with new proposals—and apparently a renewed willingness to negotiate.

Many of the tribal peoples subsisting on the fringes of rural Indian society are denied the rights to own the lands that they have lived on for millennia. The protest march, which was receiving increasing publicity in the Indian news media, with nationally prominent individuals joining the tribal peoples every day, apparently became too much for the government to resist.

The agreement it signed promises that within the next six months it will draft a National Reform Policy, after consulting with other interest groups and the state governments. However, a similar foot march in 2007 also organized by Ekta Parishad, resulted in a promise to establish a National Land Reforms Council, headed by the Prime Minister. It has never even met.

The government on Thursday agreed to establish fast-track land tribunals. In addition, it will start a national database that will record the properties that individuals own, with the intent of revealing the names of people who have purchased more lands than the laws allow. Perhaps most critically, the agreement provides for the distribution of one-tenth of one acre of land to every landless person, plus the additional land needed for housing.

Ekta Parishad gave up its demand for the establishment of land rights commissions in the various states. The national government would be constitutionally unable to promise such a thing. But the government did agree to establish a system of legal aid, and to promise it will pressure the state governments to grant homestead rights for both tribal peoples and the Dalits, formerly called the Untouchables.

According to The Hindu, Mr. Ramesh told the crowd in Agra, “Ekta Parishad should continue putting pressure not only on the Centre [the national government of India], but also on the State governments.”

While 60,000 people set out from Gwalior on the 3rd, and the march organizers had promised that the numbers would swell to 100,000 by the time the group reached Delhi, in fact only about 20,000 remained in Agra to witness Mr. Ramesh and P.V. Rajagopal, the founder of Ekta Parishad and organizer of the march, as they signed the agreement.

Mr. Rajagopal expressed his pleasure with the agreement, saying that progress is slow and gradual. He mentioned other important social improvements that have taken time to bring about in India, and said that one-tenth of an acre of land is better than nothing. The tribal people should feel safe living in huts when they own the land they are erected on. He also said, “the next step is the fight for agricultural land. We want a guarantee of one hectare of farmland for every rural household.” One hectare equals nearly two and one half acres, or 25 times the 0.1 acres promised in the current agreement.

The marchers were not all thrilled with the outcome. Malliga, one of the Paliyan women who expressed opinions about the importance of marching the previous week just before the march had started, was still there and still willing to be quoted. She was dismissive of the promise of such tiny strips of land. “What will I do with one-tenth of an acre? What can I grow on it? If I throw my seeds on that land, can my children eat from it?”

Another Paliyan woman quoted the previous week, Dhanalakshmi, had also not left the march early. Now that the protest had ended, she said that she was planning to see the Taj Mahal in Agra before returning to her village in Tamil Nadu. “But if the government does not keep its promises, we will bring more people from our villages and we will come back.” The landless Paliyans are clearly learning the power of nonviolent protests.

The powerful quake last year occurred near the border of Nepal, in the heart of

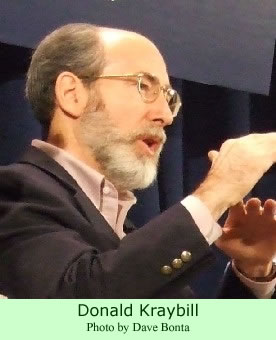

The powerful quake last year occurred near the border of Nepal, in the heart of  One of the highlights of the trial was the testimony by Donald Kraybill, eminent authority on Amish society. Kraybill, who is on the faculty of Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania,

One of the highlights of the trial was the testimony by Donald Kraybill, eminent authority on Amish society. Kraybill, who is on the faculty of Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania,