It is “a dangerous alarm,” warned Nubian activist and lawyer Salah Zaki Mourad, when the peaceful Nubians feel compelled to take up arms in order to protect themselves and their property. Yahia Zaied, a spokesperson for the Democratic Union of Nubian Youth, added to this, in a press conference last Wednesday, that the military rulers of Egypt continue to mismanage the southern part of the country, where they ignore the problems of the local people.

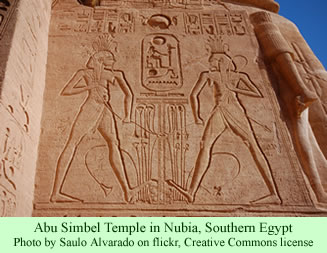

Zaied charged that the government responded inadequately to the recent collapse of a bridge over a canal in southern Nubia, near Abu Simbel. Two schools and 50 houses were flooded, but the government only sent a rescue mission 12 hours later. The Governor of Aswan, Mostapha El-Sayed, told the press after the bridge collapsed that the famed Abu Simbel monuments were unaffected. Zaied ranted: “As if Egyptians should only care about the monuments and let’s forget about the safety of the human beings…”

Zaied charged that the government responded inadequately to the recent collapse of a bridge over a canal in southern Nubia, near Abu Simbel. Two schools and 50 houses were flooded, but the government only sent a rescue mission 12 hours later. The Governor of Aswan, Mostapha El-Sayed, told the press after the bridge collapsed that the famed Abu Simbel monuments were unaffected. Zaied ranted: “As if Egyptians should only care about the monuments and let’s forget about the safety of the human beings…”

He apparently raised his points forcefully. “The Egyptian state only cares about the monuments there, only after international organizations like … UNESCO decided to save the heritage, but there was no concern for the humans who lost their culture and legacy.”

He presented the familiar argument that the Nubians want to be relocated again, since the government in the 1960s made lots of promises but the people were moved to totally inadequate places when the Aswan High Dam was built. They were relocated far from the Nile, which they see as their cultural center. The additional problem was that other, non-Nubian groups were allowed to move into the new villages that the government built, as if Egypt wanted to dilute and perhaps destroy Nubian culture. “We do not know if these were attempts to change the demography of the area or if it is a way to cause a rift between Nubians and other fellow Egyptians,” he said.

Mr. Zaied claimed that police protection has been removed from Nubia, and organized gangs of thugs are now roaming the countryside, attacking Nubians, stealing valuables, and vandalizing property. “We do have our own reasons to believe that these attacks by thugs are done in coordination with police forces,” he said. “Members of popular committees met with [the] head of Aswan Security Directorate and gave him a full list of the names of the thugs and where they live, but nothing was done since then.”

The spokesperson further argued that during three successive governments, all under the control of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the security situation in Nubia has not improved. This strongly suggests that the military rulers of Egypt are indifferent about the Nubian problems—as previous governments of Egypt have been. Representatives of several political parties attending the press conference offered their support for the Egyptian minority groups.

Other Nubian leaders joined in voicing their criticisms. Ahmed Raghed, a lawyer who is head of the Hisham Mubarak Law Center, said that the ousted regime of President Mubarak, refused to focus on minority rights and argued that the problems of the Nubians could be seen as a challenge to the unity of the Egyptian state. Anyone championing minority rights was threatening the state and inviting foreign intervention. “We need to redefine the Egyptian national fabric,” Raghed said. “We are not one entity or one culture like the ousted regime has been telling us; we are based on diversity, not homogeneity.”

Elham Eidarous, a representative of the Popular Socialist Alliance Party, seconded that argument. He said that the policy of developing the nation as if it is a unified entity has to be changed, since it has clearly failed. He made the point that international model charters of human rights uphold the principle that minority populations need to be consulted about development plans. He believes that should apply to the Nubians.

Sally Sami, a representative of the Egyptian Social Democratic Party, similarly criticized the military rulers for continuing the inappropriate policies of the Mubarak regime toward the Nubians. “We have to merge our general issues like freedom and social justice with the specific problems of minorities, citizenship, and environmental issues,” she said.

At the end of last week, the Elections Commission announced the winners of the recent rounds of polling. As expected, the Freedom and Justice Party of the Muslim Brotherhood won 47 percent of the seats in the lower house of the new parliament. But tensions remain high—protesters demand the end of the military government, which took power when Mubarak left office a year ago. The generals insist they will remain in power until a newly elected president takes over at the end of June. It is clear that the Nubians, along with many other Egyptians, are very eager for a representative government to begin.

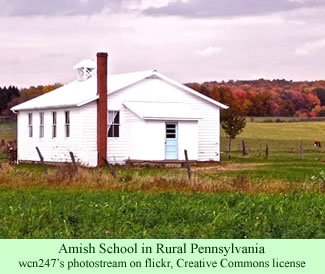

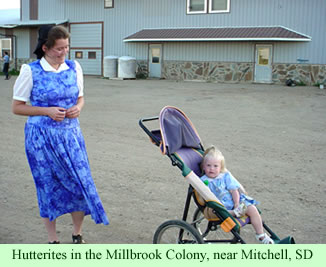

Moses Borntrager, on whose land the proposed construction was to take place, learned that an old steel bridge had been replaced by a new one up in Mendon, Missouri, 306 miles to the north, and it was sitting in a field of the farmer who had bought it for scrap. “If we’d known what we were getting into, we may not have done it,” Borntrager admitted as he surveyed the completed job recently.

Moses Borntrager, on whose land the proposed construction was to take place, learned that an old steel bridge had been replaced by a new one up in Mendon, Missouri, 306 miles to the north, and it was sitting in a field of the farmer who had bought it for scrap. “If we’d known what we were getting into, we may not have done it,” Borntrager admitted as he surveyed the completed job recently.