On June 13th, the news media in Venezuela reported that violence had occurred in a Piaroa community: the famously peaceful people had burned a local post of the National Guard. The news reports provided somewhat conflicting details, but the basic ingredients of the story were consistent.

El Universal, a major news source for the nation, reported on some communications by Liborio Guarulla, the governor of the state of Amazonas. The governor said that on Sunday evening the 12th a group of Piaroa had protested against the police. The demonstration led to the burning of some buildings on the police command post in the Piaroa community of San Juan de Manapiare. The protest followed the arrest of three Piaroa, two of whom were children.

The protest was the result of the two minors, supposedly 12 and 14 years old, having been tortured while they were in custody. The three people had been arrested that Sunday afternoon and later in the day, when the families were permitted to visit the juveniles, they saw many bruises on their bodies. They were also told that the prisoners would be transferred to the state capitol, Puerto Ayacucho.

Cesar Miguel Rondon, a radio journalist, interviewed the governor on Monday morning, the paper reported. He said that the police had accused the Piaroa of stealing, but Governor Guarulla said that Piaroa customs prohibited them from doing such a thing. Other sources indicated that shots were fired during the demonstration, though they did not report any injuries. Another report said that both the current state governor, Sr. Guarulla, and the former governor of the state, Bernabé Gutiérrez, used their Twitter accounts to reject the abuse of minors by the police.

A news post Tuesday from derechos.org provided more information about the story. The new details it revealed were that the three Piaroa were accused of stealing a motorcycle. A special commissioner for the state government, Jonathan Bolívar, said that Jose Rodriguez, a 30-year old Piaroa, and the two teenagers, ages 14 and 15 in fact, had been apprehended by the police Sunday afternoon. They were accused of stealing both the motorcycle and spare parts for it from the son of the mayor of Manapiare, Alberto Cayupare.

Sr. Bolívar went on to say that the accused are Piaroa and are not fluent in Spanish. They had answered yes when questioned about the thefts since they didn’t understand the questions. He added that during the protests, the National Guard officers fired about 80 rounds in the air—and then released the boys.

He also said that the arrests were arbitrary, and they were part of a pattern of aggression by the police against indigenous people. He added that the police action violated the human rights of the Piaroa.

The special commission had quickly gone from Puerto Ayacucho to San Juan de Manapiare on Monday to investigate the situation and to calm the indigenous community. The commissioners spoke with the people, who demanded answers as to what had happened and why. The Piaroa agreed to provide reparations and to repair some of the damage. The commission agreed that it would provide medicines for two people who had been wounded in the fracas.

The commission announced that there are severe background issues in the community—the absence of food and electricity, telephone connections that go down for long periods of time, a lack of fuel, no malaria medicine, and no drinking water. The only food available is the manioc (cassava flour) that the people grow in their own gardens.

The governor called for the lieutenant in charge of the command post to be dismissed. He said that the National Guard resolutely refuses to participate in a joint meeting to address the issues raised by the Piaroa.

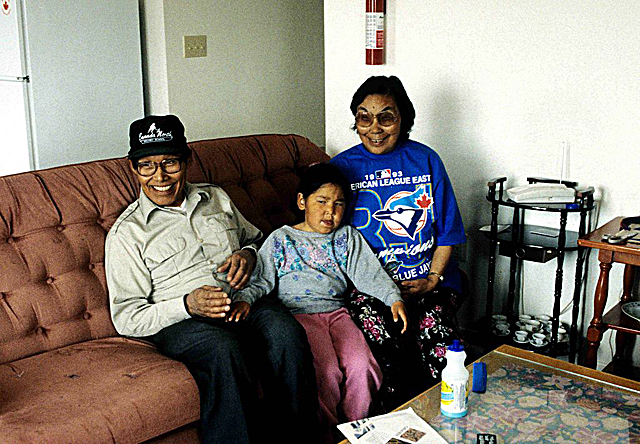

The very fact of a Piaroa community resorting to violence to confront police brutality is troubling and suggests the need for background information. A perceptive article by Overing (1989), available as a PDF on this website, provides some clues about this sort of event. Overing emphasized in her article that the Piaroa believe in tranquility so strongly that they equate good social life with a tranquil community. “Individuals are never coerced by or subjected to the violence of kinsmen and neighbours,” she wrote (p. 79).

The Piaroa communities are almost—but not completely—free of violence, she added. Violence does occur from what she called “foreign politics.” She went on to explain that while their prohibition of violence is focused on their own moral universe—the Piaroa themselves—it does not necessarily apply to outsiders.

They believe, or did while she was doing her fieldwork in their communities, that all their deaths are the result of actions by outsiders and their revenge rituals are directed at the villages of those outsiders. Of course, their society is changing, but it is notable that the people on that Sunday evening only demonstrated and burned down a building. The shots were fired by the police themselves, not the Piaroa. But it is also clear that the brutal police officials in San Juan de Manapiare are outsiders, strangers, who pushed the Piaroa too far.