A recent conference focusing on missing or murdered indigenous women and girls held in Winnipeg sought to stem the violence perpetrated against Inuit females. The round table meeting, held February 24 – 26, included government and Inuit leaders plus the families of victims. Participants spoke about the importance of finding resources that would end the continuing violence, which contrasts with the traditional ways of the Inuit society.

According to a news report about the meeting appearing in Nunatsiaq Online last week, Natan Obed, the president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, a major Inuit organization, attended the meeting. He said that all levels of government as well as Inuit non-governmental organizations need to become involved. He finds it to be “very meaningful to be in a room where all we are talking about is murdered and missing Indigenous women, and to a greater extent, the inequalities, and the need to overcome them, for our women and girls.”

Mr. Obed discussed the factors that are causing the violence, including overcrowding, addictions, inadequate housing, the absence of adequate mental health services, the lack of safe shelters, and racism in the structures of policing and justice. Solving the problem of violence is complex, but it is important to start by addressing the issues.

“It’s something we can do something about, as Inuit, as individuals,” he said. “We can make our lives better. We can make constructive choices. We can choose to follow the paths that lead us to a better society.” But they do need the support of government agencies for help in making the structural changes that will improve the situation. Mr. Obed summarized the meeting by saying that a lot of anger and emotion was expressed by family members of victims.

Monica Ell-Kanayuk, Deputy Premier of Nunavut and Minister responsible for the Status of Women, attended the conference and plans to try and make the issue a priority with the territorial legislature. She expressed impatience with the plans of the new Trudeau government to go forward by launching an inquiry into the issue. The process of having a formal inquiry, and studying its recommendations, will take years.

“The work we need to do cannot wait until inquiry recommendations come out,” she said. “Some of them we need to do now, to make changes.” Her impatience with the need for change expressed the sense of the roundtable conference. The participants at the end of the meeting prepared a listing of 20 needed outcomes, four of which the news report listed: improving the safety of women and girls in Canadian indigenous communities; anti-racist training for police, civil service employees, and people in the justice system; implementing the recommendations from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; and strengthening measures for protecting the safety of indigenous females. Inuit participants concluded the meeting with the hope that their society was reaching a turning point toward a better future for women and girls.

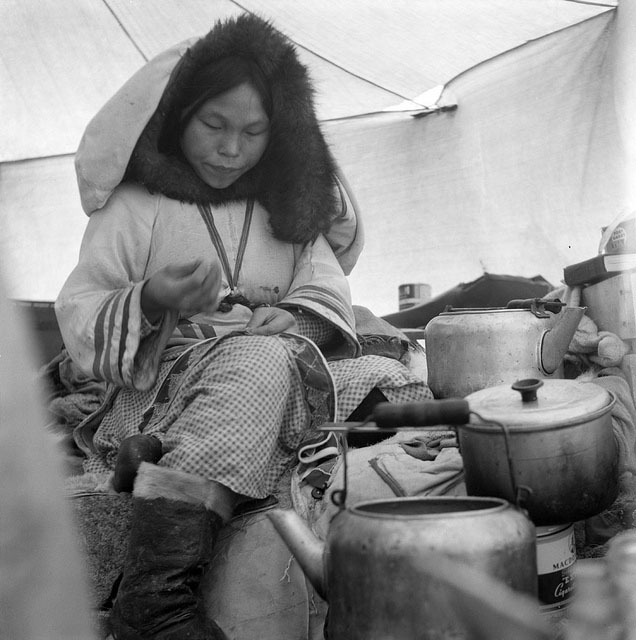

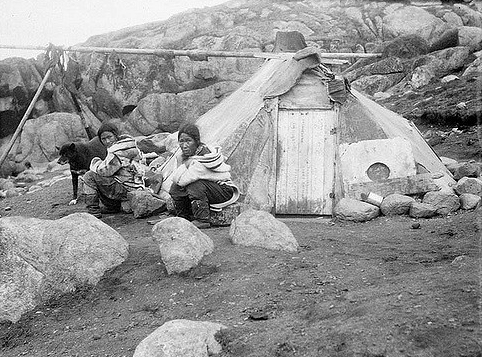

A news report last July about violence in the home against women and girls summarized the traditional male/female relationships in Inuit society when they used to live out on the land. Briggs (1974), as cited in that news story, wrote that Inuit men and women, when they lived on the land, had clearly defined separate roles, which helped to maintain social stability.

Men were the hunters and did the heavy work around the camp, while women did the lighter work, cared for the children, and made the clothing that was essential for staying warm. No one could survive without the game that the men brought in, and, equally, no one could live without the warm clothing of the women. While the men could, and did, some housework and the women did some hunting, they all felt that the work of the other was indispensable, Briggs emphasized.

Billson (2006) wrote that the move from the land into settled communities during the 1960s led to what she called “gender regimes,” situations that prompted an increase of violence against women. These incidents of violence—human rights violations—occur much more frequently than they did in the past when the Inuit lived as hunters and gatherers. She did her fieldwork in Pangnirtung, on Baffin Island, from 1988 through 2001, during which she interviewed about 100 women and 20 men.

While it was difficult for the author to be sure, it appeared to Billson’s older informants that there was much less violence against women when they still lived out on the land. There were clearly occasions of wife stealing, fighting about women, even killing, and some of the older men argued that it was acceptable in the old days for men to hit their wives. But older women argued back, as one told the author, “If you look back at our culture, assault wasn’t ‘traditional.’ There wasn’t much wife beating out on the land, because there weren’t all the social pressures (p.72).”

The older women in Pangnirtung felt that family violence, in former times, was strongly condemned. It was rare. People repeated the oft-used mantra of the traditional Inuit—that marriage wasn’t an option, it was an economic necessity, a union between a seamstress and a hunter. Both functions were essential for survival on the land. The participants in Billson’s study confirmed what other sources have stated: that the rates of violence against women have skyrocketed since they moved in from the land.

The destructive behavior of violence against Inuit women and girls has developed from a complex of conditions, including of course the fact that the people moved to settled communities. The effects of resettlement have been exacerbated by such factors as stresses in the community, marginalization, the misuse of alcohol and drugs, and the substitution of patriarchal for egalitarian values. In essence, an Inuk minister argued, the major problems have come from the outside, not from within the Inuit culture.

Billson concluded that “just as the causes of domestic violence are complex, so too are the solutions (p.81).” Her sources complained that the formal avenues of criminal justice were not really working, a situation 16 years ago that clearly is unchanged today, to judge by the report from the recent meeting in Winnipeg. One can only hope that the awareness being raised by the participants in that meeting will finally result in improvements.