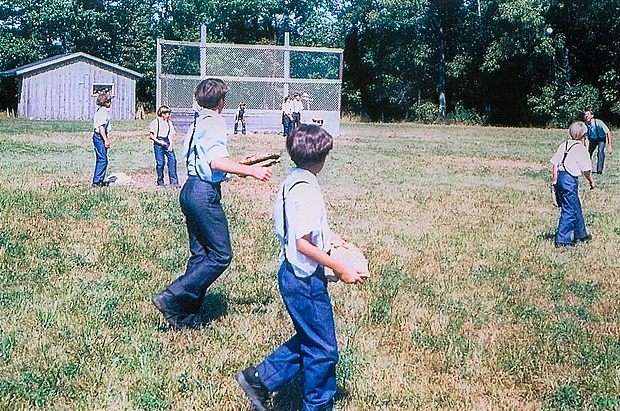

An Amish man in upstate New York has filed a lawsuit in a local court to exempt his three kids from vaccinations, which a recent state law has mandated for all school children. Among a host of news reports published on October 21 about the development, an Associated Press story reported by Syracuse.com and another by the Democrat and Chronicle from Rochester provide effective details about the issue.

The fact that the Amish man has even hired an attorney and is taking the issue into court is itself quite unusual. But the law that Jonas Stoltzfus is challenging appears to him to represent a serious threat to Amish religious beliefs. James Mermigis, the attorney for Mr. Stoltzfus, told the AP reporter that the Amish “don’t believe in vaccines. They believe if you get sick, God gives you your immune system to heal whatever sickness you have … and this is the way they’ve believed all their lives.”

Faced with the worst outbreak of measles in 27 years, New York State passed a law in June that outlawed religious objections as valid reasons for not having children vaccinated. More than 26,000 children had to be vaccinated by the end of summer and the beginning of the 2019-2020 school year or they would be forbidden from attending even the small Amish schools in their rural neighborhoods. If the kids were not vaccinated, they would not be allowed to attend any schools in the state.

Mr. Stoltzfus told the AP reporter that he was notified that his three children—12-, 10-, and 8-year old kids—would be banished from the Cranberry Marsh School in Romulus, Seneca County. The school has 24 students, all of whom are Amish. So with the help of his attorney, Mr. Stoltzfus filed suit in September in the Seneca County Court.

Jill Montag, a spokeswoman for the state Health Department, issued a statement that she could not comment about ongoing litigation but she did defend the intent of the new law. “Immunizations give children the best protection from serious childhood diseases, and the science is crystal clear that vaccines are safe and effective,” she said. In response, attorney Mermigis said that the law not only threatens the Amish community schools such as Cranberry Marsh, but it also challenges the basic Amish way of life.

The Democrat and Chronicle provides other important details, such as the statement in the lawsuit, “Despite the fact that the school is secluded and the (24) students are all Amish, the State has threatened to close the school if the students are not vaccinated against their religious beliefs.”

The lawsuit contends that the opposition to the law by Stoltzfus is based, in part, on his belief that “God made his children ‘right and good’ and to vaccinate his children is to lose faith in God.” He argued further that “to rely on a manmade solution would be an act of disbelief in the power of our God to heal and protect us.” According to the lawsuit, Stoltzfus points out that the “first Amish settlers arrived in New York State in 1831, in part because New York’s Constitution protects free exercise of religion.”

Mr. Mermigis concludes with a statement that addresses a major issue: why are they abandoning their historic belief in nonresistance and filing a lawsuit? “This is such a big deal that the Amish are actually filing a lawsuit. It’s against their principles to file a lawsuit or have any kind of confrontation, but they have been cornered and feel they have no other options,” he said.

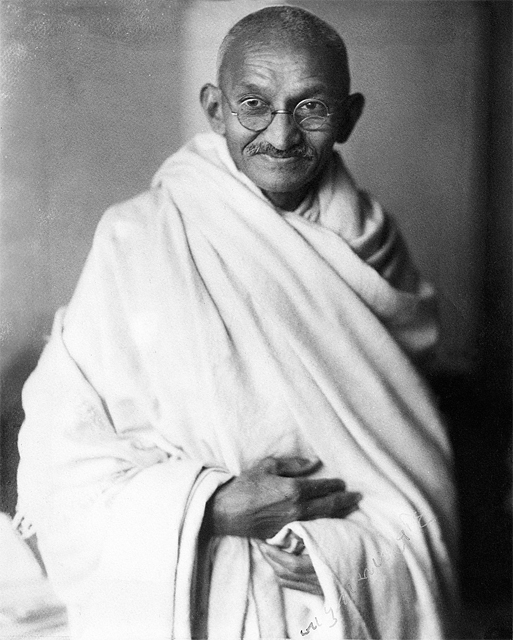

The statement by the attorney suggests the need for a more detailed explanation as to why the Amish normally don’t file suits in courts. What is it about their peacefulness that prohibits them from nonviolent legal confrontations? An article by Kidder and Hostetler (1990) provides some insights.

The authors point out that the Amish are committed to living separately from the rest of American society. They believe in being at peace and living according to nonresistance, which means settling conflicts peacefully and not contesting the will of outsiders. Internal conflicts are settled within the community and decisions reached by the group are enforced by the threat of shunning.

But much as they profess to not dealing with the outside society, Kidder and Hostetler continue, in fact there is a whole pattern of adjustment to external conflicts that, objectively, contradicts the tenets of nonresistance. In fact, a national Amish leadership has developed in the U.S. which informally has built up a wide range of relationships with outsiders in positions of power and influence, whose decisions will affect Amish lives and communities.

While these leaders are not referred to as lawyers, lobbyists, or politicians, their work and effectiveness is comparable to them. Their informal law work, lobbying, and politicking is supported by real lawyers and networks of concerned non-Amish who work to protect the Amish way of life.

If an Amishman were to be taken into court, the authors write, he would never contest charges and hire an attorney, but the Amish leaders might have an attorney friend go along, just to sit there and make sure the courts acted fairly. The lawyer would not be paid, but the Amish would give him some garden vegetables or freshly-baked bread.

Furthermore, Amish leaders expert in the laws and resourceful in finding compromises helped families all over the country during the Vietnam era. This leadership has been adroit at solving problems with outside bureaucracy by talking to top officials and finding creative legal loopholes for compromises to be reached.

For instance, since they do not believe in participating in social security, wishing instead to rely on their own communities for their security, Amish employers were stuck by the requirement to withhold social security from their Amish employee’s paychecks. The solution reached by their lay lawyers and the administrators was for the employers to make all of the employees partners in the firms.

The Amish gain protection in their cocoons by outsiders from several different perspectives: those people of Anabaptist heritage who are not members of a local Amish church; other outsiders who feel protective and helpful toward them because they represent an ideal that they can’t join; unsolicited outside charity; other rural dwellers, neighbors of the Amish, who help them and by so doing help preserve their own rural lifestyle; and, in places like Lancaster County, where the Amish presence generates several hundred million tourist dollars per year, they have a presence with the bureaucracy.

The rural Amish people have little concern or interest in these pressures, counter pressures, and maneuvering—they believe in nonresistance and, if necessary, migration to avoid problems. Even their leaders do not frame their advocacy in the terms of outsiders: rather, they see their activity as “working things out,” being helpful in resolving things, and liberating officials from their constant need to obey rules.

One might well conclude that if Kidder and Hostetler were correct, then Attorney Mermigis is absolutely right: the Amish in upstate New York are so seriously threatened by the new law that they may need to abandon at least somewhat their tradition of nonresistance in order to preserve the tenets of their faith. Or they can sell and move out of the state. The future does not look good for them.