The Kadar living in the Anakkayam Colony had to flee for their lives last August 16 when a huge landslide swept everything away right next to their homes. They’ve been homeless ever since, according to a news report published in the New Indian Express last week.

A good review of the background was provided by an article in the Outlook, an Indian magazine, last September 6. In August, Kerala was hit by the worst flooding it has experienced in a century. The big dams in the rivers had to be opened for the first time in many years and numerous tribal colonies, located in the forests near the rivers, were harmed or destroyed.

The reporter for the Outlook tried to visit the areas and communities impacted by the natural disaster but officials did all they could to hamper access by reporters. Administrators in numerous positions were dismissive of the possibility that the tribal people had been affected by the flooding. In a listing of the affected colonies, the reporter mentioned that 70 people from the Anakkayam Colony had been taken to camps.

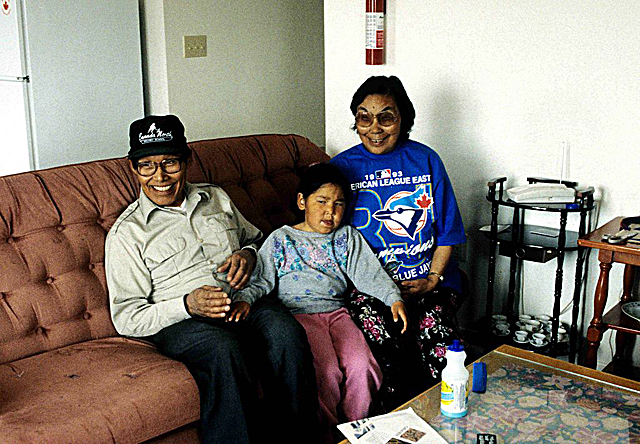

The update from June 5 focused on just the Kadar refugees from the Anakkayam Colony and how they have been faring. Not very well, in fact. The 23 families—88 people in all—are now living in temporary tents made of sheet plastic and tree branches. Immediately after the landslide they were moved to Forest Department quarters at Pokalapara but they stayed there only a month before being moved to workers’ quarters for the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB) at Peringalkuthu.

Their colony was located near the Sholayar Dam, a hydropower plant on the Chalakkudy River. They’ve been living in the KSEB facility but with the monsoon about to begin, local officials asked them to return to their own colony. The Kadar refused to go—the terror of the landslide that nearly destroyed them is still fresh in their minds. Instead, they moved out of the KSEB facility and erected a temporary camp atop a large rock near their old colony. They have been camped there for over three weeks.

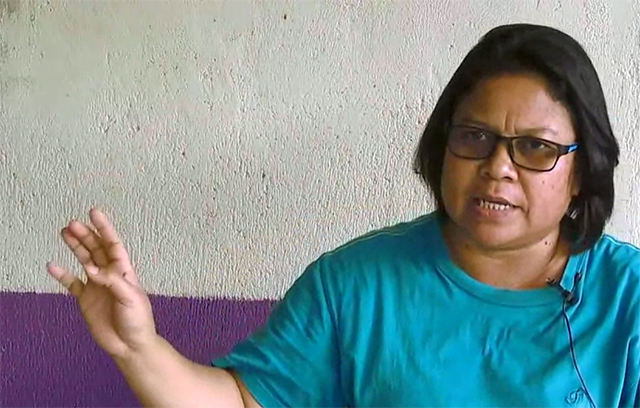

The newspaper quoted Mayilammal, a Kadar who effectively expressed the fears of the community: “The government wants us to return to the colony. It is a danger zone and living there means inviting death. If it rains for two days continuously, the entire area surrounding the colony will be washed away. How can we live there in peace?”

The highest ranking official in the Thrissur District, Ms. T.V. Anupama, the District Collector, convened a meeting to try and resolve the situation. She indicated that the Geological Survey of India has said that there is no danger of another landslide in the area near the colony. However, she obtained a contradictory opinion from the Kerala Forest Research Institute, which reported, after visiting the area, that it is not a safe spot for a tribal colony. The District Collector said that she would request an official from the State Disaster Management Authority to visit.

Meanwhile, the newspaper spoke with Raman, the Ooru Mooppan, the head of the colony. He said he had spoken with the Division Forest Officer, S.V. Vinod, who has pledged to try and help. Raman had identified a spot where a new colony might be erected, and he showed the suggested location to the DFO.

The forester approved and he agreed to give the tract of forest land to the community for their new colony. The Scheduled Tribes Department has already allocated funds to build the new houses and the basic facilities in the relocated colony. But it will take at least a year before the new colony can be built, so he urged Raman to encourage the other Kadar to return to the KSEB quarters during the interim until the new facility can be built.

One of the more interesting aspects of the story is the relationship of the Kadar with the Kerala State Electricity Board since it was that same agency that had planned and nearly gotten permission to build the Athirapilly Dam about 10 miles to the west down the Chalakkudy River from the Anakkayam Colony.

That projected dam was initiated by the KSEB in the 1980s; it was proposed to be built about 400 m. above the Vazhachal Falls on the Chalakkudy. The engineers who designed what was to be called the Athirapilly Dam estimated it would generate 163 megawatts of electric power. But the KSEB made few attempts to integrate its planning for power generation with the culture of the nearby indigenous communities.

Of the two Kadar villages closest to the planned hydropower project, Vazhachal is located less than 400 m. downstream while the other, Pokalapara, is about 4 km. upstream. At first, the Kadar in those two communities felt that government officials attached no importance to them, so they decided that their input about the dam was irrelevant.

During the period from 2006 through 2010, the project was hotly contested by major Indian environmental groups because it threatened an important riverine habitat with its unique plants and animals—and, increasingly, by the Kadar and their supporters. Despite extended strong opposition by environmentalists and supporters of the tribal society, the government of Kerala decided in 2007 that the project would move forward. The Kerala Minister for Electricity, Mr. A.K. Balan, announced that construction would begin soon on the Athirapilly Dam despite the protests.

The minister acknowledged the concerns of the Kadar people—that they might have to be moved out of their villages and could lose their traditional way of life. He said, however, in the words of one news report, that the “project will not affect any tribal family.” This website has published numerous news stories about the controversy over the dam proposal.

Mr. Balan added that the government had proposed a package for Kadar families “that might be affected by the project,” which would include a new house on an acre of land per family, plus a common area for a public health facility and a school. In other words, the government was really not going to destroy the village, but if they did, they would provide housing for the affected Kadar.

As minister not only of electricity but also of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, Mr. Balan may have had other concerns about the welfare of the Kadar. But he also announced that the proposed reservoir would have facilities for speed boating, trekking, bush walking, and other activities that should attract more tourists to the southwest coastal mountains of India. The government thus intended to provide jobs for the people affected by the development.

Similar mixed messages of great concern—and a serious lack of concern—by government officials for the welfare of the Kadar come through in the current news report about the Anakkayam Colony and its troubles.