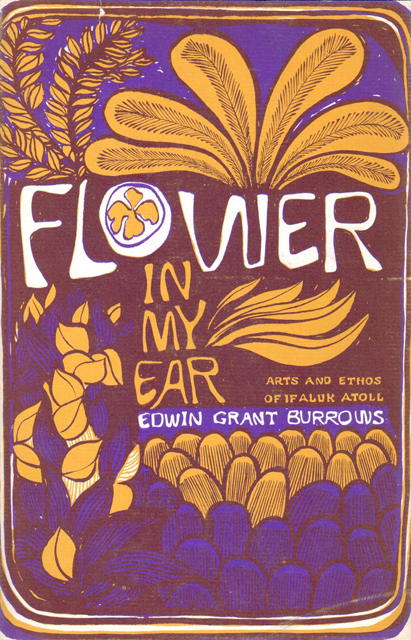

Last week the Mexican news website lanetanoticias.com published a cultural piece explaining why the art of tattooing became popular among the Ifaluk. The story of the adoption of tattooing on the island, tied in with a belief in the god Wolfat (also spelled Wolphat), is explained effectively by the journalist but it is better related, and with more detail, by Edwin Burrows in the first chapter, “Tattooing,” of his 1963 book Flower in My Ear: Arts and Ethos of Ifaluk Atoll.

Both sources indicate that tattooing is very important among the Ifaluk because it is supposed to be highly attractive to potential mates. Specifically for men who want to attract women, they must be covered with tattoos. The god Wolfat instituted the custom, according to Ifaluk legends.

Both sources indicate that tattooing is very important among the Ifaluk because it is supposed to be highly attractive to potential mates. Specifically for men who want to attract women, they must be covered with tattoos. The god Wolfat instituted the custom, according to Ifaluk legends.

One day the god looked down at the earth and saw a woman, Iloumuligeriou, and he fell for her beauty. Burrows adds the note that the Ifaluk themselves deny that this occurred right on their island, but they are not sure where it did occur. Anyway, when he entered her house at night, she awoke and asked who was there. Wolfat answered that he was a man from the sky.

She started a fire which allowed her to see him and she was struck by the black designs all over his body. Three other women also lived in the house with their husbands and when they saw the designs on the visitor’s body, they too were intrigued. They woke up their husbands and told them to look at the stranger—they wanted their men to look like that also.

In the morning, Wolfat went back to the sky. The three husbands that day took some charcoal and began covering their bodies with designs such as they had seen the night before on Wolfat. Oddly, that second night when Wolfat appeared at Iloumuligeriou’s door, he had no black designs on his skin. They were all gone. The other three women woke up and concurred with the statement of Iloumuligeriou to Wolfat. She told him to go away. She didn’t like him without his beautiful designs.

So Wolfat stepped out of the house, took the time to put on his tattoos again, and sought to reenter the home. The men of the house all awoke and, seeing Wolfat, suggested to Iloumuligeriou that she ought to marry him. So she put the idea to the god and he agreed. The next morning he showed the men of the house the art of tattooing and instructed them on how to proceed. They needed to make a needle from a wing feather of a man-of-war bird. Then they should make suitable blackening dust for decorating the skin by burning breadfruit gum and gathering the resulting soot on a smooth surface.

Melford E. Spiro, who also did fieldwork among the Ifaluk, explained in a 1951 article that Wolfat was really a trickster god, the source of much amusement to the people. For the god’s behavior was often characterized by roguish, and sometimes even hostile and petulant, behavior. Since only the Ifaluk chiefs really knew the stories of the gods well, the rest of the people just enjoyed them and delighted in the contrasts between the confrontational activities of the deity and the nearly complete absence of aggressive behavior in their community.

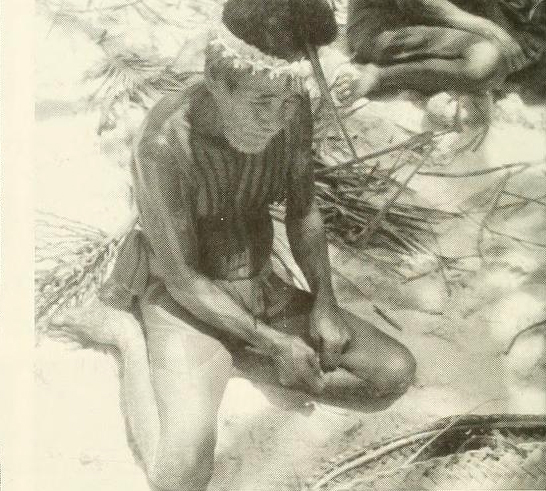

Other scientists, including biologists Marston Bates and Donald Abbott, studied the ecosystem of the island and its surrounding waters during a 1953 expedition. In their jointly-authored book about their work, Coral Island: Portrait of an Atoll, Abbott wrote in one of his chapters about his experience in getting a tattoo put on by an Ifaluk tattoo artist (p. 239 – 241). He had a set of porpoises tattooed about halfway up his right leg one day, an operation observed by a crowd of islanders.

Other scientists, including biologists Marston Bates and Donald Abbott, studied the ecosystem of the island and its surrounding waters during a 1953 expedition. In their jointly-authored book about their work, Coral Island: Portrait of an Atoll, Abbott wrote in one of his chapters about his experience in getting a tattoo put on by an Ifaluk tattoo artist (p. 239 – 241). He had a set of porpoises tattooed about halfway up his right leg one day, an operation observed by a crowd of islanders.

He hadn’t foreseen the effects of his gesture. Everywhere he went during the remaining time he had with the people, his tattoo was admired and commented upon. The sentiment of identifying with the island and its inhabitants was widely appreciated. “We were closer to them now than we had been before, and when we left, we would carry a bit of Ifaluk with us for a lifetime,” Abbott concluded (p. 241). He does not mention Wolfat, much less the issue of attractiveness to Ifaluk women.