Last November, Nubians staged protests in southern Egypt to dramatize their arguments that they’ve been cheated out of their rights and of their lands by the government. They demanded a recognition of their right to resettle their historic territory in Old Nubia, especially since it is guaranteed in the Egyptian constitution.

A news story in this website on November 24 covered only the beginnings of the November protests. Since the middle of that month, a variety of news sources have published updates about developments, including, at the beginning of last week, The Guardian.

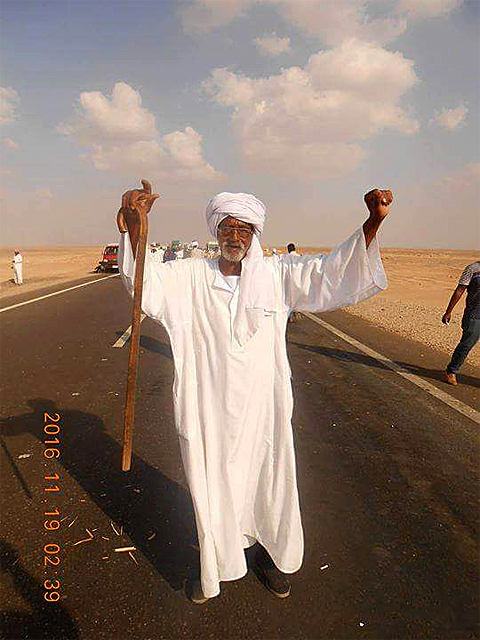

The protesters in November had been blocked from traveling the highway out into the desert to demonstrate at the Toshka Project, a huge irrigation work on land which they claim, so they had gone south in a caravan of 25 micro-buses to the historic site of Abu Simbel and set up a highway blockade there. The blockade, a major action of what they called “The Nubian Return Caravan,” started on November 19 and lasted for four days. Security forces then blockaded the blockade, preventing the protesters from having access to food or drink.

Probably because of numerous news reports about the protests, the Egyptian government decided to give the Nubians serious attention. On Wednesday, November 30, leaders of the Nubian protest movement met with Prime Minister Sherif Ismail and with Ali Abdel-Aal, speaker of the parliament, for seven hours in Cairo. The major demand of the Nubians was that the planned sale of what they consider to be their traditional territory at the Toshka Project must be cancelled.

They had made their point—the Nubians were serious about their basic issues. At their November 30 marathon sessions, the Prime Minister and the speaker of parliament decided to appoint a high-level committee which would include members of the cabinet, Nubians, and the one member of parliament who is a Nubian, Yassin Abdel Sabour from Aswan. They would be charged with revising the maps of the Toshka Project and removing disputed areas from it.

The demonstrations apparently had a serious effect on the government. Mr. Abdel-Aal announced that he and the Prime Minister would be holding meetings with other Nubian activists throughout Egypt to discuss the demands of the protesters and the steps that should be taken. The Speaker of Parliament met a second time with the Nubian leaders on December 5 and announced that he had formed a committee which would work to implement Article 236 of the Constitution of 2014—the article which gives the Nubians the right of return to their lands.

The Nubian activists have not only organized nonviolent demonstrations, they also appear to have been reasonable throughout the period. After their initial four days of blockade in the desert and the clear willingness of top government officials to meet with them, Mohamed Azmy, the head of the Nubian Union and one of the central figures in the demonstration, announced that both sides would call a halt to the protests for one month. But if the government did not make any progress, “there would be an escalation in our protests,” he warned. He also said that if Nubian demands to be allowed to return to their historic territory are not met, they will appeal to international agencies.

The Guardian report last week described some additional events. In early January, Mohamed Azmy and several other young men were detained by the government for plotting to organize additional protests. Azmy was ordered to dissolve the Nubian Union, which he headed and which spearheaded the protests. If not, he would be arrested.

Another source, also published last week, gave more details about the threats the government made against him and the Nubian Union in January. The officials demanded that Mr. Azmy must resign as head of the organization and the government must have the right to designate his replacement. “They want to get rid of me because they think that will stop the movement,” Azmy said. In response, Azmy rewrote that demand by the government, saying that the organization would continue to choose its own leadership. He resigned his position anyway, but three days later the Nubian Union voted him in again as its president.

The Guardian reporter interviewed Fatma Emam Sakory, a Nubian rights activist, for her perspective on the dispute. Ms. Sakory’s activism was described by January and February 2014 news stories in this website.

She told The Guardian rather cynically, “The case of Nubian lands shows that the government is unwilling to support its own citizens to develop their land, but prefers taking the easy way, which is selling to investors.” She added that the government was not living up to its obligations under the Egyptian constitution. Since the lands the Nubians claim as historically their own are rich in potential for mining, agriculture, and of course tourism, the government wants to take it all. Nubians have been important players in the vibrant tourist industry in Aswan and the rest of southern Egypt. “But,” Sakory argued, “if Nubians had access to it, they would do better than the government, so they could invest with us.”

If the Nubian Union and Mr. Azmy have plans for other actions to dramatize their demands, they are keeping quiet—for now.