A report published on Wednesday last week included some comments by Jumanda Gakelebone, a long-time leader of the G/wi and G//ana people of Botswana. As always, he forcefully expressed his passionate advocacy for fair government treatment of his people.

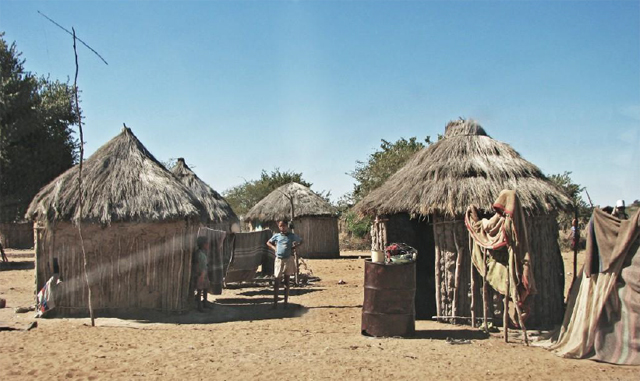

Gakelebone, 40, identified in this current story only as “secretary and spokesperson of Roy Sesana,” derides the continuing exploitation of the San people by the Botswana government. The G/wi, he explains, now subsist on herding cattle, but they receive no benefits. If a man is kicked by a cow or is otherwise injured on the job, he is laid off immediately and he receives no assistance.

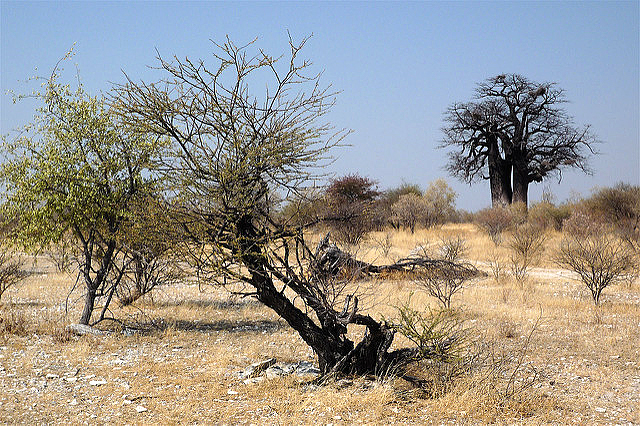

He reviews the history of the San people in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, the vast protected area in the center of the country, and how they were removed under orders from the government. The people were forced to resettle at a new settlement, New Xade, outside the CKGR, another form of government discrimination, according to Gakelebone.

“The government moved us because they wanted to make way for the hunting concession for the rich, which we the First People of the Kalahari do not benefit anything from,” he says. He goes on to complain that they were removed from their ancestral lands, in part, to make way for diamond mining concessions. “This is profound discrimination,” he argues and he points out that there is nothing the people can do about it.

While this latest story about discrimination by the Botswana government against its minority San citizens has little new to report, and long-term readers of G/wi news stories in this website would be familiar with most of the facts it advances, it does provide a useful, brief overview of the situation. It is not clear whether the author of the article interviewed Gakelebone personally or quoted his statements from other sources.

After reviewing the court cases in which the people sought the right to return to their own lands, the author perceptively quotes the founding father figure of Botswana, the first president, Sir Seretse Khama. President Khama is quoted as saying on December 15, 1969, “We must at all times avoid the creation of a special class of highly paid people in the centre while the majority of our people are living in poverty in the periphery.”