On Friday and Saturday, September 30 and October 1, a Tahitian group organized a contest to see who could prepare the best traditional feast celebrating elderly Tahitians, particularly older women. A group called the Fédération Te Ui Hotu Rau No Pare Nui and the town of Pirae, a part of Papeete, the capital city of Tahiti, got together to organize this year’s event, held in the gardens of the town hall.

An article in a major Tahitian news reporting service last week described preparations for the festival, which had not been held since 2008. The point of the contest was an ahima’a, a traditional cookout of Polynesian foods in large, underground pits. Each group entering the contest was required to have inter-generational teams of 18 people. An English-language page in a website devoted to Bora Bora, another large island in the Society Islands, provides numerous photos and an effective description of the construction and use of the ahima’a.

The point was to promote the transmission to younger people of the traditional knowledge of Tahitian elders, in this particular case the ways they prepare foods and share them with family members. The news report emphasized that other important traditional values cherished by their ancestors—sharing, teamwork and community life—were also important to convey to Tahitian families, along with the foods being prepared.

The stated objectives of the event were to develop in the neighborhoods of Pirae the knowledge and techniques of traditional cooking, to foster inter-generational exchanges through the transmission of knowledge between the elderly and young people, to value collective sharing, and to foster a strong sense of respect in the community.

The meals would be shared with the Matahiapo, elders in the community who are over 65. Plates of foods were expected to be given to around 400 people, including 300 Matahiapo and their escorts. The festival was organized to coincide with the International Day of Older Persons, declared by the United Nations to occur on October 1 annually.

Contrary to the beliefs in some other peaceful societies that older people deserved a lot of respect for their knowledge (see Biesele and Howell (1981), for instance), Levy (1973) indicated that that was normally not the case in traditional Tahitian society. While people talked about the ideal of treating parents or the pastor with respect, in reality there were no specific social or verbal forms for doing so. Instead, older persons were treated in response to the ways they acted as individuals.

The implication was that old people were more or less ignored and were provided only minimal support by their children. “When [old people] become nuisances, they are treated as nuisances,” Levy wrote (p.208). The way the elderly were treated was situational. Some people, reflecting on their deceased parents, would mention that they should have treated them better, but in fact, the anthropologist observed, they were treated the same as everyone else, depending on their behaviors, manners, and how useful they had been.

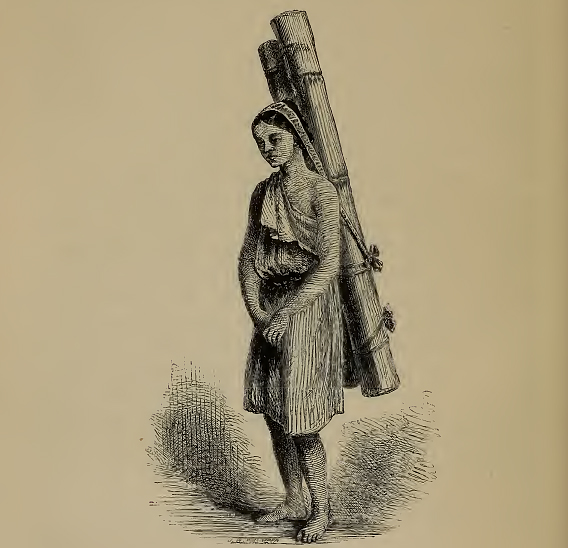

Levy concluded his analysis by writing that the elders could not count on any special respect because of their senior status. They were valued due to their specialized knowledge of special crafts, such as gardening, canoe building, magic practices or medicinal herbs, but knowledge of other traditional values and ways? People didn’t care.

In a more recent paper analyzing the relationships between masculinity and the struggles for independence in the Society Islands, Elliston (2004) pointed out that a culture of romanticizing the rural areas of Tahiti, in contrast to the urban communities, had developed in recent years. The more rural parts of the main island—Tahiti itself—and the smaller outer islands were the locations of true, traditional, Polynesian values, according to that narrative, in contrast to the hustle and bustle of the city, Papeete. Among the romantic values Tahitians proposed for themselves and their traditional rural society, she wrote, were hard work, friendliness, sharing, and the notion that children are “raised to respect their elders (p.622).” In essence, she was agreeing with Levy regarding attitudes toward the elderly.

The outsider has to wonder, however, if developing a narrative of respect for older people is gaining ground among urban Tahitians, and is that going to help reinvent a tradition of peacefulness? Perhaps such a new tradition, including respect for older persons, will differ somewhat from the conditions that Levy wrote about, but the development is still worth watching.