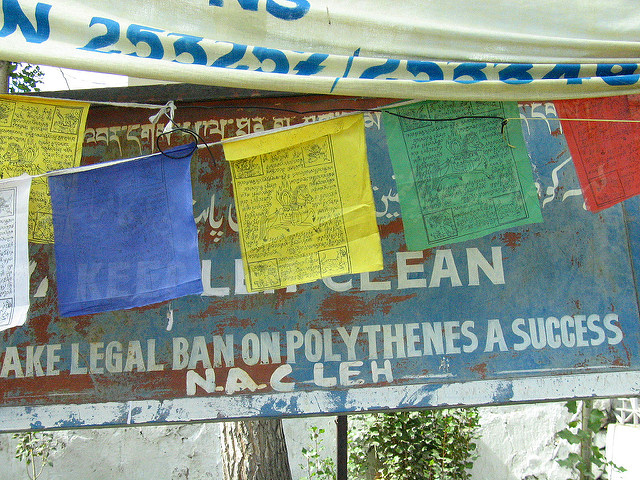

The use of polyethylene bags is a growing problem in the mountains of Northern India, except for Ladakh where the people have been able to get rid of them. Why are the Ladakhi so concerned about their natural environment that they embrace the idea of banning the polluting bags when others who live in equally beautiful places such as the Kashmir Valley do not? Several news stories and editorials recently have compared the two regions of India and their attitudes toward trash.

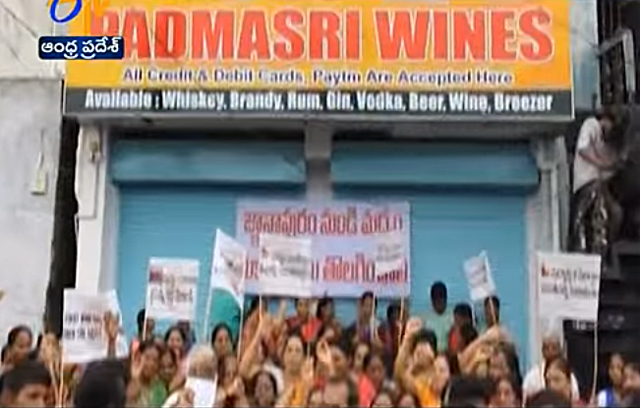

A news report back in March credited the success of the anti-polyethylene bag movement in Ladakh on the Ama Tsogspa groups, the so-called Mothers’ Alliances. (British and Indian media refer to polyethylene bags as “polythene bags.”) The Ama Tsogspa groups, concerned women who get together in Ladakhi villages and towns to tackle major community issues, are responsible for the success of the anti-polyethylene movement. Use of the bags was banned throughout Ladakh back in 1998 largely because of their efforts.

An editorial in June this year from the Kashmir Valley ranted about the Kashmiri disregard for existing laws and court orders that also ban the bags. Police have seized large quantities of them: in 2015, more than 1,000 kg of polyethylene were seized but the people continued to ignore the ban. “The administration speaks a lot about the awareness and punishment but the fact is that they have not been able to ban polythene even after so many years,” the article declared. After providing many details of various Kashmiri attempts to ban the bags, the author concluded that the only way to succeed was for civil society and the government to unite in eradicating the menace. The Kashmiri people need to emulate the Ladakhi.

Another opinion piece published in Kashmir on August 9 went into even greater detail about the heaps of garbage in the cities of Jammu and Kashmir, a major component of which is “the pollution caused by littering of polythene [which] is becoming … a huge environmental disaster.” Even in small towns named in the article, tons of polyethylene are sold every day. But, the article concluded, the people of Ladakh have done better. “Having realized the hazards of polythene to the environment, they have [stopped] its use for good.” Although Ladakh is far behind the rest of the state of Jammu and Kashmir in terms of formal education, the people of Ladakh “are true leaders,” the author wrote.

In comparing the success of the Ladakhis in better preserving their natural environment, none of those accounts explained why the Ladakhi people have such a strong concern for their surroundings. The more scholarly accounts of the Ladakhi, however, do provide important clues about the reactions of the people toward their cold, mountain desert—and imply some reasons for their rejection of the plastic bags.

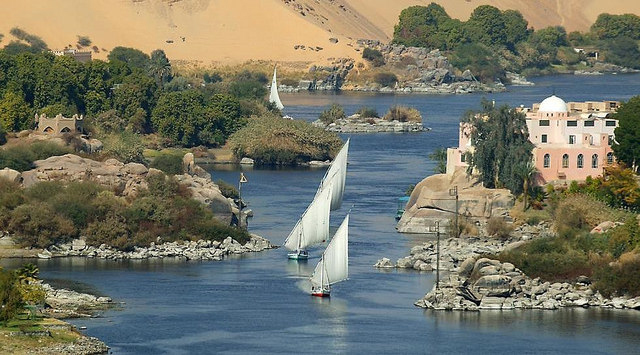

Mann (1978) captured the relationship of the Ladakhi toward their surroundings in an article in which he explained the ways their harsh environment affects their values, religious beliefs and social structures. He described the difficult weather, the high elevation, the uneven landscape, and the limited natural resources as conditions in which humans have a hard time understanding their environment. As a result, the people have turned to spiritual beliefs for explanations and security.

Their land is marked by many religious structures and supernatural spirits that reflect their fear of, and awe for, nature. “The relationship of reverence is established with hills, fields, water sources, etc.,” he wrote (p.72). The deities that they connected with the natural features of the land were acknowledged and sometimes worshiped, and appeased so that they would continue to support human endeavors.

Mann summarized the situation in his book The Ladakhi: A Study in Ethnography and Change (1986). Because of the harsh environment of Ladakh, helpfulness and cooperation among families are essential for survival. He went on to say that the Ladakhi are entirely peaceful, an outgrowth, in his view, of both the Buddhism they practice and the environmental conditions of their country, which discourage aggression and encourage docile behavior.

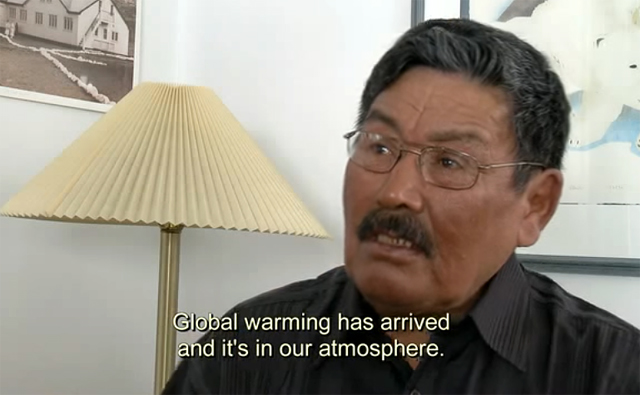

A more recent book on Ladakh by Mingle (2015) included human-caused pollution as well as relations with the gods in an analysis of the Ladakhi and their surroundings. The focus of the book was on the declining snowfall and on a corresponding drop in the water supply for Kumik, a village in the Zanskar region of Ladakh. While the situation could simply be caused by global climate change, the people of the village, the Kumikpas, decided it was more serious than that.

As the problem grew worse, they began blaming themselves—they felt that the Iha, the local gods, had become angry with them. They were not praying as much as they should, and they had gotten too focused on making money and on their own selfish desires. The Kumikpas felt that the gods were punishing them for their careless ways of polluting the earth. The only way to appease the gods would be to improve their behavior.

Although none of those works addressed the issue of polyethylene bags, the Ladakhi clearly link the health of their natural environment with their bedrock spiritual values. The rampant pollution the plastic bags produce must symbolize a disregard not only for the earth they live on but for their religious values as well. It’s no wonder that the writers in Kashmir are envious of the people of Ladakh and their commitment to the natural environment.