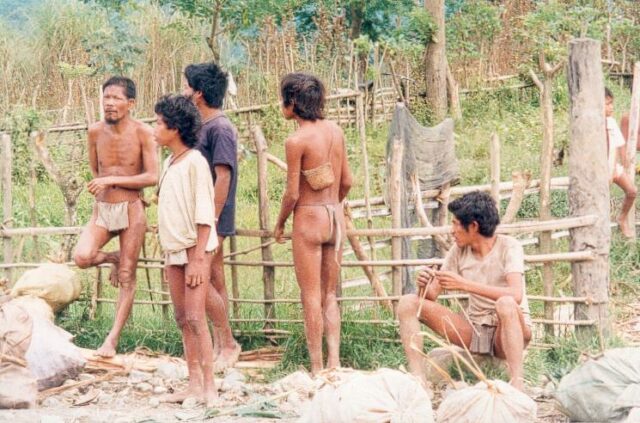

The Yanadi of coastal Andhra Pradesh are increasingly dependent for their income on fish raised in cages along the Krishna River estuary. A brief report in The Hindu on February 8 described the actions by agencies and scientists involved in fostering this novel way for the poor, landless people to secure a better living.

Raising Asian sea bass and Indian pompano in cages, in a process called “mariculture,” another term for fish farming, provides a living for a number of Yanadi, many of whom used to be dependent on fishing alone. Several agencies have given scientific and technical assistance—and financial help. The Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI-Visakhapatnam), the M.S. Swaminathan Research Foundation (MSSRF-Chennai), and the National Fisheries Development Board (NABARD) are among the supporters.

About ten years ago, the CMFRI began experimenting with cage fish farming at the behest of a progressive farmer in the Krishna area, Mr. T. Raghu Sekhar. As a result of their successes, about 80 floating fish cages have been installed in the estuary for the use of the Yanadi and other tribal people, with the costs supported by CMFRI. “Mariculture is a lifeline for the landless poor,” said Raghu Sekhar.

The Hindu quoted R. Ramasubramanyan, a researcher with MSSRF, who said that the support by the agencies for the new venture, by providing supplies and training, “will yield more results in mariculture, apart from uplifting the landless families.”

A news story posted on December 4 covered the Yanadi efforts to help protect the nesting olive ridley sea turtles that swim ashore to lay their eggs along the coast of the state. It appears as if the Yanadi commitment to effectively managing their coastal environment extends to their harvesting of fish as well.

The available ethnographic literature on the Fipa doesn’t provide much useful background information. The most interesting work is Smythe’s book

The available ethnographic literature on the Fipa doesn’t provide much useful background information. The most interesting work is Smythe’s book