A dramatic announcement by a Piaroa interest group last week not only outlined their opposition to illegal mining activity within their territory, it also denounced the presence of armed groups that violate their peaceful ethos. The manifesto was published on March 9 on the website of the Observatory of Political Ecology of Venezuela.

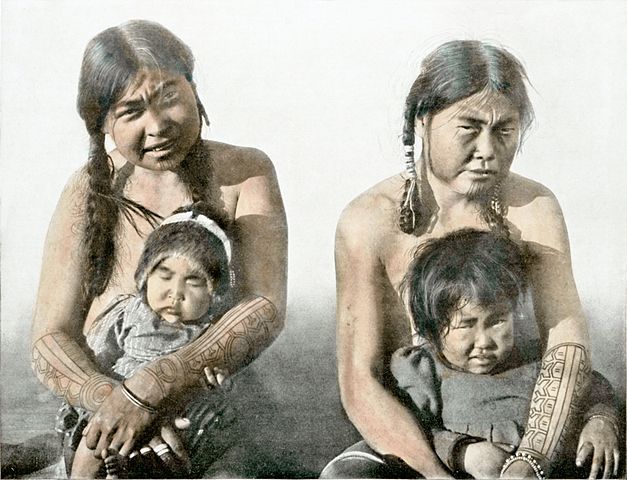

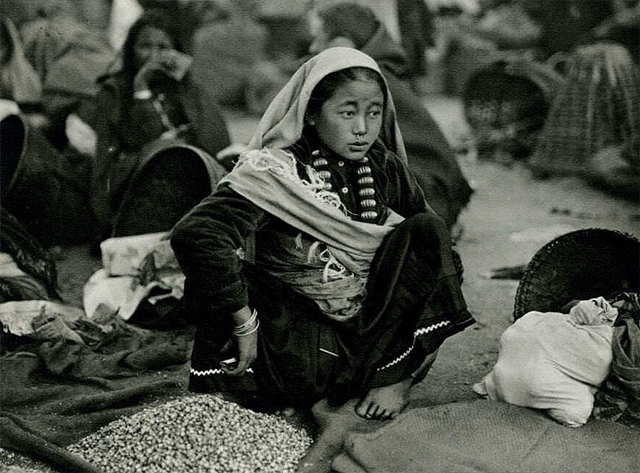

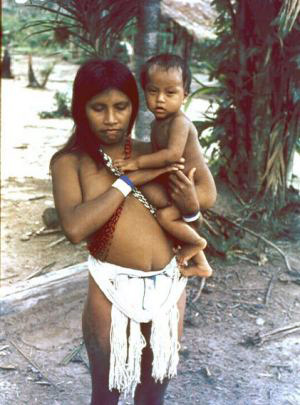

People from four different Piaroa areas of Venezuela’s Amazonas state gathered in the Pendare community of the Autana municipality to prepare their declaration. They write that they are the “heirs, possessors and guardians of their territories” in southcentral Venezuela, people who base their ways on their worldview, which their pronouncement describes as peaceful. Throughout the document, the indigenous term used is “Uwottüja,” an alternate name for the Piaroa.

The document reminds a reader from the United States about the American Declaration of Independence: both documents justify their statements in a similar fashion. Recall the famous “he has” sentences describing the wrongdoings of the King of England toward his subjects in the British colonies. The Piaroa write in their declaration of complaints, “tired that governments do not attend to our problems or needs…”

And what do they propose to do about the situation? “We have decided to defend ourselves, by our own means, from this silent invasion, making use of our constitutional right to defend the sovereignty of our Nation, as indigenous Venezuelan citizens, we have decided to defend our Uwottüja territory.” They make it clear that they will defend their territory and their rights in entirely peaceful ways. Their document sets out the specifics of their concerns, some of which need to be described.

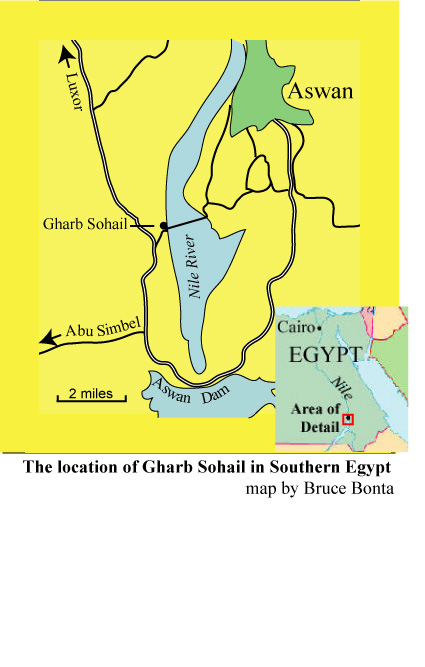

The first demand is that they should be recognized as the “original people” of the four major rivers of the Amazonas state—the Autana, the Cuao, the Sipapo, and the middle sector of the Orinoco. As such, they are the guardians of their territories, responsible for the biocultural resources of the land and water.

Furthermore, they reject the illegal mining that goes on in their territory. They declare their opposition to all other illegal activities, such as using the territory for the shipment of drugs.

They demand that all armed people, whether Venezuelans or internationals, who are increasingly fomenting conflicts with the indigenous people must be prevented from using their territory. The writers deplore the fact that some of their indigenous brothers have been induced to join those armed gangs.

They demand that the governments of Venezuela and of Amazonas state re-activate the commissions that were working to demarcate the indigenous territory. Those commissions have not been functioning for at least ten years. Even though the Piaroa consider their territory to be rightfully theirs to manage and use, having the government declare the territory officially as theirs would be very helpful.

Next, the compliers deal with their widely-known peacefulness with a statement beginning, “That as a Uwottüja Indigenous People, peaceful people, that we do not accept any form of violence….” Therefore, the armed people must be expelled from their territory for they are opposed to any warfare with armed gangs, with invaders from across the border in Colombia, or with anyone else.

They indicate at the close of the document that 287 Piaroa met in Pendare on February 26 to agree on the declaration of rights. They intend to monitor the situation and collect evidence with their video cameras at such spots as the beach at the mouth of the Autana River.

It will be interesting to see if a self-prepared declaration such as this will help the Piaroa without any follow-up violence or warfare. In essence, the American colonies declared their independence from England and then fought a protracted war to really secure it. But are other approaches possible? Can a society pledged to avoiding violence succeed in gaining its rights through non-violent means?